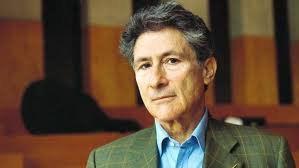

PROFESSOR SAID says that his aim is to set works of art of the imperialist and post-colonial eras into their historical context. "My method is to focus as much as possible on individual works, to read them first as great products of the creative and interpretive imagination, and then to show them as part of the relationship between culture and empire."He says he has not "completely worked out theory of the connection between literature and culture on the one hand, and imperialism on the other"; he just hopes to discover connections. He says it is useful to do this because "by looking at culture and imperialism carefully ... we shall see that we can profitably draw connections that enrich and sharpen our reading of major cultural texts." Indeed, it is more than useful; it must be obligatory if he is right in saying that the "major, I would say determining, political horizon of modern Western culture [is] imperialism," and that to ignore that fact, as critical theory, deconstruction and Marxism do, "is to disaffiliate modern culture from its engagements and attachments."

Having set himself this vast task, which would cover virtually all Western history for the past three centuries, Professor Said must cut it back to manageable size: he will deal with parts of the British and French empires only, and culture will be represented by a small number of novels and one opera. Thereby the proposed Herculean labors come down to looking for references to the colonies in some works of fiction.

That occupies only the first two of four chapters. He then turns to the question of how decolonization is reflected in the culture of newly independent nations. In turn, this large subject is cut down to "one fairly discrete aspect of this powerful impingement"--that is, the work of intellectuals from the colonial or peripheral regions who wrote in an "imperial language" and who reflected on western culture. So we pass from Jane Austen's mentions of Antigua to Caribbean, Bengali and Malaysian views of imperialist practices. It is an original idea to put them together, but already the reader feels that the book is beginning to sprawl. That feeling grows when this third chapter deviates into a theory about decolonization as a political process, and about the difference between independence and liberation. By the fourth and last chapter Professor Said has quite lost the thread and we are treated to a familiar denunciation of "American cultural imperialism." The only Western works of art mentioned here are "Dynasty," "Dallas," and "I Love Lucy" and there is no suggestion that they refer to empire in the way Kipling and Conrad did. There is much perfervid sweeping generalization about Western intellectuals' treatment of the Third World, notably of Islam during the Gulf War, balanced (if that is the word) by frank denunciations of the lack of liberty in that same Third World, notably again in Islam.

So what we have here is a book on literature plus two or three pamphlets that contain much ranting, all barely held together in a bad case of intellectual sprawl. For the casual reader, there is plenty of interesting erudition and some sensitive literary analysis too much heated political diatribe. For students--supposing this book attains the trendy academic status of Said's Orientalism--there is only confusion, engendered by shifting definitions of such key words as "imperialism" and by Said's propensity to extravagant generalization, of this sort: "Without empire, I would go so far as saying, there is no European novel..." These vast generalizations (which alternate with angry attacks on other people's unwarranted "totalizations") are followed by passages of hedging and qualification, where Said affects to be moderate and cautious, but he soon resumes his extreme claims as though he had conceded nothing. One gets the impression that he wants to occupy all possible positions on a subject, always readying himself to deal with criticism by retorting, "Oh, but I say that too!"

Perhaps the basic difficulty and source of confusion is that "and" in his title. The reality is that the spread of British people and their civilization to the American colonies, toCanada, Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere was a cultural phenomenon or it was nothing. That we can also call it imperialism does not mean that we thereby get two distinct things, one called culture and the other called empire, so that we can now ask how one "intersects with" or determines or causes the other. This is what happens when, for example, people ask whether ideology is determined by the economy. In order to get two things so distinct that one could determine the other, we have to find a completely non-ideological economy, and since that is impossible the discussion becomes confused.

There is a perfectly logical way of fudging this sort of problem: give each term so narrow a definition that you do get two distinct things which might then interact. For instance, you decree that the economy is "money-grubbing" and ideology is "highfalutin' ideas." You then have a genuine question: how do high-falutin' ideas disguise or glorify money-grubbing. The trouble is, conceived so narrowly, the problem loses much of its interest and descends to petty "unmasking." This is the method Said adopts in the first part of his book. Imperialism is given the narrow definition of stealing territory: "The actual geographical possession of land is what empire in the final analysis is all about." Culture is given an even narrower definition: "a realm of unchanging intellectual monuments, free from worldly affiliations." So now the supposed problem is how the activity of stealing land from natives shows up in, is romanticized or excused in, apparently apolitical works of art. It should be clear in advance that, first, such a narrow matter could be described as "imperialism and culture" only in a fit of grandiloquence; second, it will dredge up a list of allusions, hints, and mere mentions so long as it deals with works of art and not political tracts; third, it will culminate in So What?

The narrow view of imperialism as naked territorial rapacity cannot, of course, be sustained for long. When Said wants to denounce U.S. foreign policy, he has to call it "imperialism without colonies" and "cultural colonialism," silently abandoning his own theory. Well before that he finds he cannot even account for classic imperialism, because he thinks there is a problem about how "Britain's great humanistic ideas, institutions, and monuments, which we still celebrate ... co-existed so comfortably with imperialism." He is genuinely puzzled that the land of Jane Austen, John Stuart Mill, and Keats could run an empire, which is why he goes looking for tell-tale signs of guilt about empire in the highest reaches of British culture. Blinded by his narrow view of it, he cannot see that imperialist culture included not only authoritarian, commercial, and supremacist strains, but also libertarian, reformist, and co-operative forces dedicated to ideals of trusteeship, devolution (after the shock of the loss of the American colonies) and eventual partnership. Even more important, it was these latter forces that in the end won out over the likes of Curzon and Churchill; without always actually meaning to decolonize, they made so many adjustments, concessions, and reforms that empire was eroded from within. As P.J. Marshall has said, "An imperial identity ebbed away over a long period without a sudden disorientating crisis of loss." That is how scores of nations were freed from European imperialism, whereas Said's narrow view could only explain (in part) exceptional cases like Algeria, where land was tenaciously clung to.

SAID DESCRIBES his aim thus: "my subject [is] how culture participates in imperialism yet is somehow excused for its role." Or again: "One of my reasons for writing this book is to show how far the quest for, concern about, and consciousness of overseas dominion extended not just in Conrad but in figures we practically never think of in that connection like Thackeray and Austen and how enriching and important for the critic is attention to this material..." Well, what does he deliver?

He takes Jane Austen's Mansfield Park and turns up six references to Antigua and one to slavery. Now, in fact that is extremely interesting, as long as you can resist (as, alas, Professor Said cannot resist) the temptation to jump to earth-shattering, world-historical conclusions. When Jane Austen tells us that Sir Thomas Bertram's business trips are to the Caribbean and that it is not done to mention slavery in his house, she is hinting that that marvelous world of decorum, comfort, and respectability to which Fanny Price aspired was financed in part by plantation slavery. I am ashamed that I missed that point when I read the novel and watched the television series, and I am grateful to Said for stressing it. But he only knows because jane Austen told him, so his airs of unmasking the imperialist villain, of smoking out perfidy from ethereal aesthetic creation are hardly warranted.

Thackeray is promised as another example, in the passage I have quoted. He goes on being promised and appearing in lists of imperial writers, but nothing ever comes of it but this: one character in Vanity Fair is described as a nabob and there are sundry other "mentions" (Said's word) of India in the novel. Said concludes, "All through Vanity Fair there are allusions to India but none is anything more than incidental ... Yet Thackeray and, I would argue, all the major English novelists of the mid-nineteenth century, accepted a globalized world-view and indeed could not (in most cases did not) ignore the vast overseas of British power."

The rest of his evidence for this large conclusion is equally slender: Rochester's deranged wife in Jane Eyre was a West Indian, and was not Abel Magwich in Great Expectations transported to Australia? A character in Henry James's Portrait of a Lady took a trip to Algeria and Egypt! The pickings are so slim that Said admits that through much of the nineteenth-century empire was "only [a] marginally visible presence in fiction." He even takes to complaining that it is not mentioned enough, because the wretched imperialists took it for granted, like their servants who feature only as props in novels. None of this deters him from his grand conclusion: there could be no novel without empire. Why not? Because of "the far from accidental convergence between the patterns of narrative authority constitutive of the novel on the one hand, and, on the other, a complex ideological configuration underlying the tendency of imperialism." This central mystery is never explained. One example is proffered (to Said's credit, diffidently): "Richardson's minute constructions of bourgeois seduction and rapacity" in Clarissa resemble "British military moves against the French in India occurring at the same time."

In one of those accesses of mock moderation, Said adds, "I am not trying to say that the novel--or the culture in the broad sense--|caused' imperialism, but that the novel, as a cultural artifact of bourgeois society, and imperialism are unthinkable without each other ... imperialism and the novel fortified each other to such a degree that it is impossible, I would argue, to read one without in some way dealing with the other." No such "moderate" conclusion has been established, but Said is soon back to claiming that "we can see it [the novel] as participating in England's overseas empire" and that British imperial "power was elaborated and articulated in the novel." Therefore, we are bidden to re-read "the entire archive of modern and pre-modern European and American culture," no less, in order to discover "the centrality of the imperial vision." It will be worth the effort because we shall be rewarded with such nuggets of knowledge as that the Wilcox family in Howard's End owned rubber plantations! And the plague in "Death in Venice" came from the East! So did the wandering Jew, Leopold Bloom! Thus and thus does fiction fortify imperialism.

Said then tries his hand at opera, choosing the easy target of Verdi's Aida. The Cairoopera house had opened in 1869 as part of the celebrations for the inauguration of theSuez Canal and although Verdi declined the invitation to write a hymn for that occasion, he soon after agreed to write an opera for the Khedive, one based on an Egyptian story. So Said is correct to see Aida as a quintessential imperialist party-piece, a slap-up night out for the Suez speculators in the phony European sector of Cairo. Aida, he says, is "not so much about but of imperial domination."

But Said cannot rest there. He soars aloft: "The cultural machinery [of spectacles like Aida] ... has had an aesthetic as well as informative effect on European audiences ... such distancing and aestheticizing cultural practices ... split and then anaesthetize the metropolitan consciousness. In 1865 the British governor of Jamaica, E.J. Eyre, ordered a retaliatory massacre of Blacks for the killing of a few whites..." Not everyone in Britain would condemn Eyre; Ruskin, Carlyle, and Arnold would not. Their attitude reminds Said of American popular approval of the Gulf War: "making America strong and enhancing President Bush's image as a leader took precedence over destroying a distant society," even so soon after "two million Vietnamese were killed" and while "Southeast Asia is still devastated."

At this point the bemused reader is apt to rub his eyes and run his finger along the text, for how did we get, literally from one page to the next, from Aida in Cairo in 1871, to a Jamaican massacre in 1865, to Vietnam and then to the Gulf War? We did it because Said reasons that Western art about an Oriental subject anaesthetizes Western consciousness to the point where at least some people are brought to excuse massacres of natives and foreign wars. And that is one way culture is connected to imperialism.

At least, it is one way Said slides from literary criticism to political tub-thumping. The whole book takes just such a slide partway through the third chapter. He has been discussing the interesting fiction and theory coming out of the new nations, and he notes that some of it is highly critical, not so much of the former imperialists as of the nationalist rulers who have succeeded them. He readily agrees that decolonization has, in many countries, led only to a change in the color of the oppressors, to "an appalling pathology of power," to dictatorships, oligarchies, and one-party systems. He lists Third World countries where human rights are denied and asks, is this the only alternative to imperialism? No, there is another answer to imperialism besides nationalism, "a deeper opposition" and "a radically new perspective."

Astonishingly, the radically new perspective turns out to be an idea that Frantz Fanon published over thirty years ago: true liberation, as distinct from mere national independence, can only be won in a war of cleansing violence that will set the peasants, the damned of the earth, against not only the imperialists but their own urban compatriots. In the course of this war of liberation, there will occur "an epistemological revolution," and "a transformation of social consciousness." Said has a long section on Fanon's Les Damnes de la Terre (1962) which consists of ecstatic paraphrase. The "shift from the terrain of nationalist independence to the theoretical domain of liberation," Said declares, requires "a fertile culture of resistance whose core is energetic insurgency, a |technique of trouble'" and sometimes armed insurrection.

Said calmly says of this liberationist literature that "there is an understandable tendency ... to see in it a blueprint for the horrors of the Pol Pot regime." Indeed there is, and Said does nothing to counter that tendency except to assert that the violence invoked is only "tactical." That is one of those fine distinctions that gets overlooked in the killing fields. Moreover, as one might expect from a fine connoisseur of fiction who ventures into political theory, Said is vague about whether this miraculous cultural rebirth in violent war has actually occurred anywhere (apart from Cambodia, I suppose) or whether it could happen anywhere else. "Algeria was liberated, as were Kenya and the Sudan," he says but is careful not to hold them up as successful cases of rebirth. He finally concedes that Fanon's ideas failed because he had no answer to nationalism.

Why spend so much time on him then, trumpeting him as the inventor of the alternative to both imperialism and nationalism? Said's reply to that seems to be that liberationist ideas survive as "an imaginative, even utopian vision which reconceives emancipatory (as opposed to confining) theory and performance." Besides that, such ideas encourage "an investment neither in new authorities, doctrines, and encoded orthodoxies, nor in established institutions and causes, but in a particular sort of nomadic, migratory, and anti-narrative energy." It is not clear what that means but it does not sound like practical politics.

I suspect, basing myself on passages scattered throughout this book, that Said is being coy here, even evasive. I believe he has in mind a specific case where Fanon's ideas about cleansing violence and cultural rebirth still have a chance. That case is the Palestinian intifada in the occupied territories of Israel.

He has spoken of the imperialist West's "regional surrogates" in the Middle East in a context that makes plain he has Israel in view. The Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands thereby becomes a case of imperialism, and anyhow it answers to his definition of imperialism as stealing land from natives. Consequently, the Palestinian intifada becomes "one of the great anti-colonial uprisings of our times." It ranks with such vast causes as the ecological and women's movements as an example of a worldwide "elusive oppositional mood and its emerging strategies," a mood that must "hearten even the most intransigent pessimist." It is one of those mass uprisings such as occurred in thePhilippines and South Africa, which feature "impressive crowd-activated sites, each of them crammed with largely unarmed civilian populations, well past the point of enduring the imposed deprivations, tyranny and inflexibility of governments that had ruled them for too long." Those stone-throwing Palestinian youths are memorable for the "resourcefulness and the startling symbolism of the protests," just like the heroic mobs of South Africa and communist Eastern Europe.

This comes to rating the intifada pretty highly, but there is nothing absurd in that, nor anything ignoble. If Said does not say outright that the Palestinian cause is the last hope of Fanon's liberationist ideals, it might be because he is not sure. When he wrote this book, he had not visited the land of his birth since 1947 (although he was a member of the Palestine National Council, the parliament-in-exile, from 1977 to 1991), but since then he has gone back for a visit. He is now composing a memoir about it. It might tell us something interesting, particularly if it relies on what he sees rather than on the theories proposed in Culture and Imperialism.

The Source of Culture and Imperialism

Edward W. Said's latest work, Culture and Imperialism is indebted to Gramsci in several respects, even if less obviously than The World, the Text and the Critic. Gramsci unfinished essay on the southern question is one of Said's points of reference as a work that sets the stage for the critical attention given in the Prison Notebooks to the "territorial, spatial and geographical foundations of life." Said's analyses of a wide range of literary texts, which he uses as sources for understanding the dynamics of politics and culture in their connections with the whole imperialist enterprise, can be read as fulfillments of the historical materialist premises outlined in fragmentary form in both the Prison Notebooks and the Letters From Prison.

Unlike Gramsci, Said does not adhere explicitly to Marxism, nor does he identify himself with any one political current of movement. Nevertheless, underlying his work is a set of theoretical principles and practical stances that are certainly in harmony with a Gramscian world view. Certain tensions in Said's relationship to Marxism have been noted by the Indian Marxist Aijaz Ahmad, who argues in his book In Theory that Said has not really assimilated the materialist and revolutionary principles undergirding Gramsci's work. Ahmad frames his critique of Said within the boundaries of a rather strict interpretation of Marxism in his commitment to socialism as the foundation on which to build a genuinely oppositional culture. He is skeptical of Said's foregrounding of anti-imperialism and the principle of "liberatory" politics that avoids explicitly socialist partisanship.

Literary Allusions in Cutlure and Imperialism

Said's message is that imperialism is not about a moment in history; it is about a continuing interdependent discourse between subject peoples and the dominant discourse of the empire. Despite the apparent and much-vaunted end of colonialism, the unstated assumptions on which empire was based linger on, snuffing out visions of an "Other" world without domination, constraining the imaginary of equality and justice. Said sees bringing these unstated assumptions to awareness as a first step in transforming the old tentacles of empire. To this end he wrote Culture AND Imperialism.

Let’ have a sense of Edward Said's view of empire and colonialism in the cultural and literary context. The first passage I want to share with you is on pp. 88-89, in which he describes Fanny and Sir Thomas from Jane Austen's Mansfield Park. I'm going to assume that you are not familiar with the novel, which is the story of Fanny's being taken into Sir Thomas' life at Mansfield Park, where she eventually adjusts into the role of mistress of the estate.

Fanny was from a poor line of the family, and her parents are not scrupulous and capable and good and sensible managers of wealth. These are skills which Fanny acquires when she goes, at 10, to live at Mansfield Park. Edward Said notes that Jane Austen devotes little time to the colonies or the management thereof. But he identifies throughout the novel, her proclivity to accept the colonies as a proper means of maintaining the wealth of England. Said also notes that England, unlike the Spanish and to some extent the French, was more focussed on long-term subjugation of the colonies, on managing the colonized peoples to cultivate sugar and other commodities for the English. Said uses the literature of that period to illustrate the extent to which acceptance that subjugated peoples should in fact engage in such labor, and that the proceeds from that labor should support the English.

Said quotes the following passage describing Fanny's visit to the home she left at 10:

"Fanny was almost stunned. The smallness of the house, and thinness of the walls, brought every thing so close to her, that, added to the fatigue of her journey, and all her recent agitation, she hardly knew how to bear it. Within the rom all was tranquil enough, for Susan (Fanny's younger sister) having disappeared with the others, there were soon only her father and herself remaining; and he taking out a newspaper---the accustomary loan of a neighbour, applied himself to studying it, without seeming to recollect her existence. The solitary candle was held between himself and the paper, without any reference to her possible convenience, but she had nothing to do, and was glad to have the light screened from her aching head, as she sat in bewildered, broken, sorrowful contemplation.

"She was at home. But alas! it was not such a home, she had not such a welcome, as---she checked herself; she was unreasonable. . . . A day or two might shew the difference. Sheonly was to blame. Yes, she thought it would not have been so at Mansfield. No, in her uncle's house there would have been a consideration of times and seasons, a regulation of subject, a propritey, an attention towards every body which there was not here." [Footnote omitted.]

Quoted at p. 88 of Culture AND Imperialism.

Said's comment on this passage highlights the extent to which he sees in Austen's writing the reflection of empire:

"In too small a space, you cannot see clearly, you cannot think clearly, you cannot have regulation or attention of the proper sort. The fineness of Austen's detail ("the solitary candle was held between himself and the paper, without any reference to her possible convenience") renders very precisely the dangers of unsociability, of lonely insularity, of diminished awareness that are rectivied in larger and better administered spaces."

As I contemplate Said's description, I am confounded once again by Spivak's insistence that suffering from racism is not the same as suffering colonialism. I do understand her insistence that the colonized are objectified as inevitably unworthy of enjoying the product of their own labor, and that the colonized have essentially nothing to gain. But when she suggests that those suffering from racism, or any form of ethnocentrism or sexism, I suppose, should rely on the access they have to the presentation of validity claims in the dominant discourse, I become skeptical. Throughout Said's analysis, I am constantly reminded that the mere illusion of access to "the goodies" simply distracts us from an understanding that there are very real ceilings to our aspirations. (Robert K. Merton spoke of these "three myths" of American society already in 1935, in Social Theory and Social Structure.

To describe workers under racism and other ism's as having real stakes that the colonized do not have, I think is to delude ourselves. If awareness is, in fact, the first, best step we can find towards peace and understanding, then I find such delusions dangerous. jeanne

A few pages later in Culture AND Imperialism, Said points out the importance of this deeper and more complex criticism he has offered us of Austen's Mansfield Park. Most criticism, from whatever it's theoretical perspective, does not go into what Said calls "the structure of attitude and reference." [At p. 95.] And Said does not intend this postcolonial perspective to replace other perspectives. He expects such criticism to be used in addition to traditional literary criticism. His emphasis is on how much more there is of importance to the slight references to the colonial world made in great literature. He suggests that it is precisely in great literature that we are able to see the internal structure of conflict over a morality that, though not acceptable in the polite society of the empire, has permeated the thinking of those for whom the great literature was written. Jane Austen's sensibility could not deal with the issue of the "slave trade," which, in Mansfield Park, was met with "dead silence." Edward Said's comment: "In time there would no longer be a dead silence when slavery was spoken of, and the subject became central in a new understanding of what Europe was." [At p. 96.]

Jane Austen and Conrad

The cherished axiom of [Jane] Austen's unwordliness is closely tied to a sense of her polite remove from the contingencies of history. It was Q. D. Leavis (1942) who first pointed out the tendency of scholars to lift Austen out of her social millieu, gallantly allowing her gorgeous sentences to float free, untainted by the routines of labor that produced them and deaf to the tumult of current events. Since Leavis, numerous efforts have been made to counter the patronizing view that Austen, in her fidelity to the local, the surface, the detail, was oblivious to large-scale struggles, to wars and mass movements of all kinds. Claudia Johnson(1988), for example, has challenged R. W. Chapman's long-standing edition of Austen for its readiness to illustrate her ballrooms and refusal to gloss her allusions to riots or slaves and has linked this writer to a tradition of frankly political novels by women. It is in keeping with such historicizing gestures that [Edward] Said's Culture and Imperialism insists on Mansfield Park's participation in its moment, pursuing the references to Caribbean slavery that Chapmen pointedly ignored. Yet while arguing vigorously for the novel's active role in producing imperialist plots, Said also in effect replays the story of its author's passivity regarding issues in the public sphere. Unconcerned about Sir Thomas Bertram's colonial holdings in slaves as well as land and taking for granted their necessity to the good life at home, Said's Austen is a veritable Aunt Jane - naive, complacent, and demurely without overt political opinion.

I will grant that Said's depiction of Austen as unthinking in her references to Antigua fits logically with his overall contention that nineteenth-century European culture, and especially the English novel, unwittingly but systematically helped to gain consent for imperialist policies (see C, p. 75). [The novel] was, Said asserts, one of the primary discourses contributing to a 'consolidated vision,' virtually uncontested, of England's righteous imperial prerogative (C, p. 75). Austen is no different from Thackeray or Dickens, then, in her implicit loyalty to official Eurocentrism. At the same time, Said's version of Austen in particular is given a boost by the readily available myth of her 'feminine' nearsightedness... This rendering of Austen is further enabled, I would argue, by Said's highly selective materialization of her... [Mansfield Park] is, in fact, almost completely isolated from the rest of Austen's work. If the truth be told, Said's attention even to his chosen text is cursory: Austen's references to Antigua (and India) are mentioned without actually being read...

But this picture of Austen is disembodied in not only a textual but also a larger social sense. Though recontextualized as an Eglish national in the period preceding colonial expansion, Austen's more precise status as an unmarried, middle-class, scribbling woman remains wholly unspecified. The failure to consider Austen's gender and the significance of this omision is pointed up by Said's more nuanced treatment of Conrad. According to Said, Conrad stands out from other colonial writers because, as a Polish expatriate, he possessed 'an extraordinarily persistent residual sense of his own exilic marginality' (C, p. 24). The result is a double view of imperialism that at once refutes and reinforces the West's right to dominate the globe. As Said explains, 'Never the wholly incorporated and fully acculturated Englishman, Conrad therefore preserved an ironic distance [from imperial conquest] in each of his works' (C, p. 25). Of course Austen was not, any more than Conrad, 'the wholly incorporated and fully acculturated Englishman.' Lacking the franchise, enjoying few property rights (and these because she was single), living as a dependent at the edge of her brother's estate, and publishing her work anonymously, Austen was arguably a kind of exile in her own country. If we follow out the logic of Said's own identity politics, Austen, too, might therefore be suspected of irony toward reigning constructions of citizenship, however much, like Conrad, she may also in many respects have upheld them. The goal of this essay is to indicate where and, finally, to suggest why Said so entirely misses this irony. My point, I should stress, is not to exonerate Austen of imperialist crimes. Surely Said is right to include her among those who made colonialism thinkable by constructing the West as center, home, and norm, while pushing everything else to the margins. The question I would raise is not whether Austen contributed to English domination abroad but how her doing so was necessarily inflected and partly disrupted by her position as a bourgeois woman.